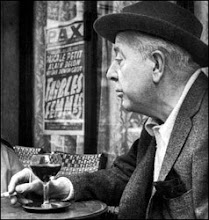

Charles Chaplin is the most famous filmmaker in the world.

The enthusiasm of the audiences - it's difficult to imagine its proportions today (we would have to extend the cult of Eva Peron in Argentina to the entire world) - made Chaplin the most popular man in the world in 1920.

Charlie Chaplin, abandoned by an alcoholic father, spent his first years in the anguish of seeing his mother taken away to an asylum, and experienced the terror of being picked up by the police. He was a nine-year-old vagrant hugging the walls of Kensington Road, as he wrote in his memoirs, living "...on the lowest levels of society." This has often been described and commented on, but I'm returning to it because all the comments may have caused the extreme harshness of his life to be lost sight of, and we really ought to take note of how much explosiveness there is in total misery.

In his chase films for Keystone, Chaplin runs faster and farther than his music-hall colleagues because, if he is not the only filmmaker to have described hunger, he is the only one who knew it at first hand. This is what his audiences all over the world felt when his films began to be circulated in 1914.

I am almost of the opinion that Chaplin, whose mother was certifiably mad, came close to complete alienation and that he escaped thanks to his gift of mime, a gift he inherited from her. In recent years there have been serious studies of children who have grown up in isolation, in moral, physical, or material distress. The specialists describe autism as a defense mechanism. But everything that Charlie does is precisely a defense mechanism. When Bazin explains that Charlie is not antisocial but asocial, and that he aspires to enter society, he defines, in almost the same terms as Kanner, the schizophrenic and the autistic child: "While the schizophrenic tries to resolve his problem by quitting a world of which he had been a part, autistic children come progressively to the compromise which consists in having only the most careful contact with a world in which they have been strangers from the beginning." To take a single example of displacement (the word recurs constantly in Bazin's writing, as it does in Bruno Bettelheim's work about autistic children, The Empty Fortress), Bettelheim says: "The autistic child has less fear of things and will perhaps act on them, because it is persons, not things, who seem to threaten his existence. Nevertheless, the use that he makes of things is not that for which they were conceived."

And Bazin: It seems that objects accept Charlie's help only when they are outside the meaning society has assigned to them. The most beautiful example of such a displacement is the famous dance of the loaves of bread in which the objects' complicity explodes into a free choreography.

In today's terms, Charlie would be the most "marginal" of the marginal. When he became the most famous and richest artist in the world, he felt constrained by age or modesty, or perhaps by logic, to abandon his vagabond character, but he still understood that the roles of "settled" men were forbidden him. He has to change his myth, but he must remain mythic.

Chaplin dominated and influenced fifty years of cinema to the point that he can be clearly distinguished behind Julien Carette in La Regle du feu; just as we see Henri Verdoux behind Archibaldo de la Cruz, we find the little Jewish barber who watches his house burn in The Great Dictator standing twenty-six years later behind the old Pole in Milos Forman's The Firemen's Ball.

His work is divided into two parts, the vagabond and the most famous man in the world. The first asks, Do I exist? and the second tries to answer, Who am I? All of Chaplin's work revolves around the major theme of artistic creation, the question of identity.

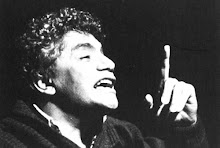

François Truffaut

1932 - 1984

![[...]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjeNC2Kyxd34r2LuofHe9-vdXHeHwG3_2NhVmIOTlK2moU0Q4R7taMlS8iMmQgEl1-NdaRsPrLdREzfQZYKfUgjslwLZUZe67dAfFBREu-YRx6WGX-vAUt5eJT4_-lFwT4dGzGCQQ/s220/11798115_858304687558226_1857652538_n.jpg)