Under capitalism the social status of the poet has changed. Shakespeare was attached to the Earl of Leicester. Although a bourgeois in origin and outlook, his status was feudal Milton, on the other hand, was for many years a Commonwealth official, and foreign secretary to Cromwell. His status was bourgeois. But there was the closest union between his politics and his poetry. After the Restoration there was a partial return to the semi-feudal conditions of patronage. Poets like Pope and Gay enjoyed the hospitality of the landed gentry, who subscribed to their poems and employed them as secretaries. But with the Industrial Revolution all feudal survivals were finally swept away. Poetry became a commodity, the poet a producer for the open market, and with a decreasing demand for his wares. During the past half-century capitalism has ceased to be a progressive force, the bourgeoisie has ceased to be a progressive class, and so bourgeois culture, including poetry, is losing its vitality. Our contemporary poetry is not the work of the ruling class — what does big business care about poetry? — but of a small and isolated section of the community, the middle-class intelligentsia, spurned by the ruling class but still hesitating to join hands with the masses of the people, the proletariat, who alone have the strength to break through the iron ring of monopoly capitalism. And so bourgeois poetry has lost touch with the underlying forces of social change. Its range has contracted — the range of its content and the range of its appeal. It is no longer the work of a people, or even of a class, but of a coterie. Unless the bourgeois poet can learn reorientate his art, he will soon have nobody to sing to but himself Shakespeare’s masterpieces were written to be declaimed with voice and gesture before a crowd, sweeping a thousand heartstrings with the magic of a word. This has gone out of our poetry. Even Shakespeare is no longer a draw. I am not forgetting all that has been achieved in purely literary forms, such as Shakespeare’s own Sonnets or Keats’s Odes. But all poetry is in origin a social act, in which poet and people commune. Our poetry has been individualised to such a degree that it has lost touch with its source of life. It has withered at the root.

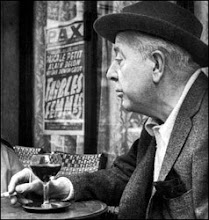

George Thomson

1903 - 1987

![[...]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjeNC2Kyxd34r2LuofHe9-vdXHeHwG3_2NhVmIOTlK2moU0Q4R7taMlS8iMmQgEl1-NdaRsPrLdREzfQZYKfUgjslwLZUZe67dAfFBREu-YRx6WGX-vAUt5eJT4_-lFwT4dGzGCQQ/s220/11798115_858304687558226_1857652538_n.jpg)