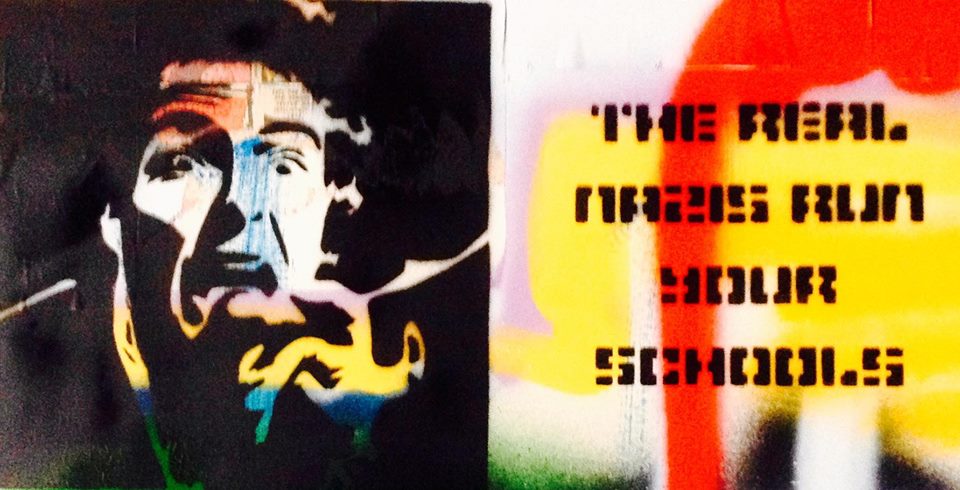

Capitalist realism as I understand it cannot be confined to art or to the quasi-propagandistic way in wich advertising functions. It is more like a pervasive atmosphere, conditioning not only the production of culture but also the regulation of work and education, and acting as a kind of invisible barrier constraining thought and action.

If capitalist realism is so seamless, and if current forms of resistance are so hopeless and impotent, where can an effective challenge come from? A moral critique of capitalism, emphasizing the ways in which it leads to suffering, only reinforces capitalist realism. Poverty, famine and war can be presented as an inevitable part of rality, while the hope that these forms of suffering could be eliminated easily painted as naive utopianism. Capitalist realism can only be threatened if it is shown to be in some way inconsistent or untenable; if, that is to say, capitalism's ostensible realism turns out to be nothing of the sort.

Needles to say, what counts as realistic, what seems possible at any point in the social field, is defined by series of political determinations. An ideological position can never be really successful until it is naturalized, and it cannot be naturalized while it is still thought of as a value rather than a fact. Accordingly, neoliberalism has sought to eliminate the very category of value in the ethical sense. Over the past thirty years, capitalist realism has successfully installed a business ontology in wich it is simply obvious that everything in society, including healthcare and education, should be run as a business.

Environmental catastrophe is one such Real. At one level, to be sure, it might look as if Green issues are very far from being unrepresentable voids for capitalist culture. Climate change and the threat of resource-depletion are not being repressed so much as incorporated into advertising and marketing. What this treatment of environmental catastrophe illustrates is the fantasy structure on which capitalist realism depends: a presupposition that resources are infinite, that the earth itself is merely a husk which capital can at a certain point slough off like a used skin, and that any problem can be solved by the market. [...] Yet environmental catastrophe features in late capitalist culture only as a kind of simulacra, its real implications for capitalism too traumatic to be a assimilated into the system. The significance of Green critiques is that they suggest that, far from being the only viable political-economic system, capitalism is in fact primed to destroy the entire human environment. The relationship between capitalism and eco-disaster is neither coincidental nor accidental: capital's need of a constantly expanding market, its growth fetish, mean that capitalism is by its very nature opposed to any notion of sustainability.

But Green issues are already a contested zone, already a site where politicization is being fought for. In what follows, I want to stress two other aporias in capitalist realism, which are not yet politicized to anything like the same degree. The first is mental health. Mental health, in fact, is a paradigm case of how capitalist realism operates. Capitalist realism insists on treating mental health as if it were a natural fact, like weather (but, then again weather is no longer a natural fact so much as a political-economic effect. Madness was not a natural, but a political, category. [...] In his book The Selfish Capitalist, Oliver James has convincingly posited a correlation between rising rates of mental distress and the neoliberal mode of capitalism practiced in countries like Britain, the USA and Australia. In line with Jame's claims, I want to argue that it is necessary to reframe the growing problem os stress (and distress) in capitalist societies. Instead of treating it as incumbent on individuals to resolve their own psychological distress, instead, that is, of accepting the vast privatization of stress that has taken place over the last thirty years, we need to ask: how has it become acceptable that so many people, and especially so many young people, are ill? The mental health plague in capitalist societies would suggest that, instead being the only social system that works, capitalism is inherently dysfunctional, and that the cost of it appearing to work is very high.

The other phenomenon I want to highlight is bureaucracy. [...] The persistence of bureaucracy in late capitalism does not in itself indicate that capitalism does not work - rather, what it suggest is that the way in which capitalism does actually work is very different from the picture presented by capitalist realism.

In part, I have chosen to focus on mental health problems and bureaucracy because they both feature heavily in an area of culture which has becoming increasingly dominated by the imperatives of capitalist realism: education.

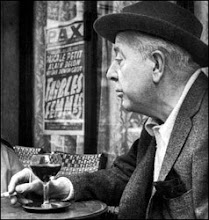

Mark Fisher

1968 - 2017

![[...]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjeNC2Kyxd34r2LuofHe9-vdXHeHwG3_2NhVmIOTlK2moU0Q4R7taMlS8iMmQgEl1-NdaRsPrLdREzfQZYKfUgjslwLZUZe67dAfFBREu-YRx6WGX-vAUt5eJT4_-lFwT4dGzGCQQ/s220/11798115_858304687558226_1857652538_n.jpg)