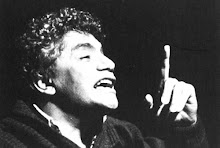

The first book I ever read of Paul Goodman - I was seventeen - was a collection of stories called The Break-up of Our Camp, published by New Directions. Within a year I had read everything he'd published, and from then on started keeping up. There is no living American writer for whom I have felt the same simple curiosity to read as quickly as possible anything he wrote, on any subject. That I mostly agreed with what he thought was not the main reason; there are other writers I agree with to whom I am not so loyal. It was that voice of his that seduced me - that direct, cranky, egotistical, generous American voice.

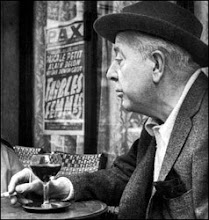

Paul Goodman's voice is the real thing. There has not been such a convincing, genuine, singular voice in our language since D. H. Lawrence. Paul Goodman's voice touched everything he wrote about with intensi ty, interest, and his own terribly appealing sureness and awkwardness. What he wrote was a nervy mixture of syntactical stiffness and verbal felicity; he was capable of writing sentences of a wonderful purity of style and vivacity of language, and also capable of wri ting so sloppily and clumsily that one imagined he must be doing it on purpose. But it never mattered. It was his voice, that is to say, his intelligence and the poetry of his intelligence incarnated, which kept me a loyal and passionate addict. For twenty years he has been to me quite simply the most important American writer. He was our Sartre, our Cocteau.I gained energy from reading Paul Goodman.

He was one of that small company of writers, living and dead, who established for me the value of being a writer and from whose work I drew the standards by which I measured my own.

Susan Sontag

1972

![[...]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjeNC2Kyxd34r2LuofHe9-vdXHeHwG3_2NhVmIOTlK2moU0Q4R7taMlS8iMmQgEl1-NdaRsPrLdREzfQZYKfUgjslwLZUZe67dAfFBREu-YRx6WGX-vAUt5eJT4_-lFwT4dGzGCQQ/s220/11798115_858304687558226_1857652538_n.jpg)