A more powerful and direct link with socialism came through the applied and decorative arts. The link was direct and conscious, especially in the British Arts and Crafts movement, whose great master William Morris (1834 – 96) became a sort of Marxist and made both a powerful theoretical as well as an outstanding practical contribution to the social transformation of the arts. These branches of the arts took as their point of departure not the individual and isolated artist but the artisan. They protested against the reduction of the creative workercraftsman into a mere "operative" by capitalist industry, and their main object was not to create individual works of art, ideally designed to be contemplated in isolation, but the framework of human daily life, such as villages and towns, houses and their interior furnishings. Indeed, the Arts and Crafts movement and its development, "art nouveau", pioneered the first genuinely comfortable bourgeois lifestyle of the nineteenth century, the suburban or semi-rural "cottage" or "villa", and the style, in various versions, also found a particular welcome in young or provincial bourgeois communities anxious to express their cultural identity – in Brussels and Barcelona, Glasgow, Helsinki and Prague. Nevertheless, the social ambitions of the artist-craftsmen and architects of this avantgarde were not confined to supplying middle-class needs. They pioneered modern architecture and town-planning in which the social-utopian element is evident – and these "pioneers of the modern movement" often, as in the case of W.R. Lethaby (1857 – 1931), Patrick Geddes and the champions of garden cities, came from the British progressive-socialist milieu. On the continent its champions were closely associated with social democracy.

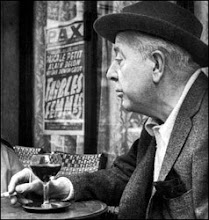

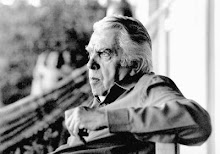

Eric Hobsbawm

1917 - 2012

![[...]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjeNC2Kyxd34r2LuofHe9-vdXHeHwG3_2NhVmIOTlK2moU0Q4R7taMlS8iMmQgEl1-NdaRsPrLdREzfQZYKfUgjslwLZUZe67dAfFBREu-YRx6WGX-vAUt5eJT4_-lFwT4dGzGCQQ/s220/11798115_858304687558226_1857652538_n.jpg)