In the social production of their existence, men enter into relations which are determined, necessary, independent of their will; these relations of production correspond to a given stage of development of their material productive forces. The totality of these relations of production constitutes the real foundation upon which a legal and political superstructure arises and to which definite forms of social consciousness correspond.

Now, in the present phase of our history, productive forces have entered into conflict with relations of production. Creative work is alienated; man does not recognise himself in his own product, and his exhausting labor appears to him as a hostile force. Since alienation comes about as the result of this conflict, it is a historical reality and completely irreducible to an idea. If men are to free themselves from it, and if their work is to become the pure objectification of themselves, it is not enough that “consciousness think itself”; there must be material work and revolutionary praxis. When Marx writes: “Just as we do not judge an individual by his own idea of himself, so we cannot judge a... period of revolutionary upheaval by its own selfconsciousness,” he is indicating the priority of action (work and social praxis) over knowledge as well as their heterogeneity. He too asserts that the human fact is irreducible to knowing, that it must be lived and produced; but he is not going to confuse it with the empty subjectivity of a puritanical and mystified petite bourgeoisie. He makes of it the immediate theme of the philosophical totalisation, and it is the concrete man whom he puts at the center of his research, that man who is defined simultaneously by his needs, by the material conditions of his existence, and by the nature of his work-that is, by his struggle against things and against men.

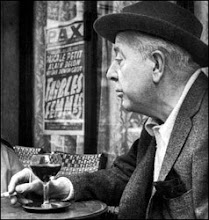

Jean-Paul Sartre

1905 - 1980

![[...]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjeNC2Kyxd34r2LuofHe9-vdXHeHwG3_2NhVmIOTlK2moU0Q4R7taMlS8iMmQgEl1-NdaRsPrLdREzfQZYKfUgjslwLZUZe67dAfFBREu-YRx6WGX-vAUt5eJT4_-lFwT4dGzGCQQ/s220/11798115_858304687558226_1857652538_n.jpg)