Elite recruits to communism should not obscure the numerically very substantial proportion - in Britain and the USA a majority - the anti-fascist and communist students who did not come from the British "public school" or the elite US "prep schools" and "Ivy League" universities, and those intellectuals who did not come from universities at all. In the history of 1930s Marxism institutions like the London School of Economics and City College, New York played a role as important or more important than did Oxford and Yale. Among the British Marxist historians of the generation of the 1930s and 1940s, the majority of those who later became well known came from grammar schools, and indeed often from provincial non-conformist Liberal or Labour backgrounds, though several of them converged with the elite in the ancient universities of Oxford and Cambridge. In France, the narrow ladder of meritocratic promotion brought sons of Republican lower officials and primary school-teachers to the higher levels of left-wing intellectualism as well as the sons of professional families with a long tradition of higher academic education. In short, in the countries of established liberal democracy, where fascism made little mass appeal to the middle and lower middle classes, the recruitment of antifascist intellectuals was relatively broad.

This is particularly obvious among the large number of non university intellectuals. We know that 75% of the members of the British Left Book Club (which at its peak reached 57,000 members and a readership of a quarter of a million) were whitecollar workers, lower professionals and other non-academic intellectuals. This public was certainly similar to the mass public for cheap and intellectually demanding paperbacks which was also discovered in Britain in the middle 1930s by Penguin Books, whose main intellectual series was edited by men of the left. The bulk of the passionate champions of folk-music and jazz in both Britain and America – they contained a disproportionate percentage of young communists in Britain – were also to be found on the borders of the skilled class of workers, subaltern technicians and professions and the middle class, as well as among students. The growing field of journalism, advertising and entertainment provided employment for both non-university intellectuals and such university intellectuals as did not choose to make a career in one of the traditional public or private professions – particularly in countries like Britain and the USA, where entry into these new fields was comparatively easy. New centres of organised anti-fascist and left-wing activity therefore developed in such centres of the film industry (which was then the major mass medium) as Hollywood, and in mass journalism of a non-political or not specifically reactionary kind.

Anti-fascism was therefore not confined to an intellectual elite. It included those librarians and social workers in the USA to whom communism made a particularly strong appeal. It included those whom the elite despised: "the discontented magazine-writer, the guilty Hollywood scenarist, the unpaid high school teacher, the politically inexperienced scientist, the intelligent clerk, the culturally aspiring dentist". It thus reflected the democratisation of the intelligentsia.

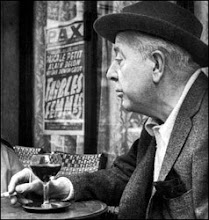

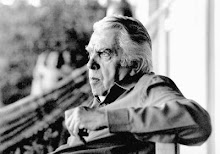

Eric Hobsbawm

1917 - 2012

![[...]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjeNC2Kyxd34r2LuofHe9-vdXHeHwG3_2NhVmIOTlK2moU0Q4R7taMlS8iMmQgEl1-NdaRsPrLdREzfQZYKfUgjslwLZUZe67dAfFBREu-YRx6WGX-vAUt5eJT4_-lFwT4dGzGCQQ/s220/11798115_858304687558226_1857652538_n.jpg)