Cosmic rays, mainly electrons and protons, have bombarded the Earth for the entire history of life on our planet. A star destroys itself thousands of light-years away and produces cosmic rays that spiral through the Milky Way Galaxy for millions of years until, quite by accident, some of them strike the Earth, and our hereditary material. Perhaps some key steps in the development of the genetic code, or the Cambrian explosion, or bipedal stature among our ancestors were initiated by cosmic rays.

Neutron star matter weighs - about the same as an ordinary mountain per teaspoonful - so much that if you had a piece of it and let it go (you could hardly do otherwise), it might pass effortlessly through the Earth like a falling stone through air, carving a hole for itself completely through our planet and emerging out the other side - perhaps in China. People there might be out for a stroll, minding their own business, when a tiny lump of neutron star plummets out of the ground, hovers for a moment, and then returns beneath the Earth, providing at least a diversion from the routine of the day.

The awesome power of the neutron star is lurking in the nucleus of every atom, hidden in every teacup and dormouse, every breath of air, every apple pie. The neutron star teaches us respect for the commonplace.

A star like the Sun will end its days, as we have seen, as a red giant and then a White dwarf. A collapsing star twice as massive as the Sun will become a supernova and then a neutron star. But a more massive star, left, after its supernova phase, with, say, five times the Sun’s mass, has an even more remarkable fate reserved for it - its gravity will turn it into a black hole.

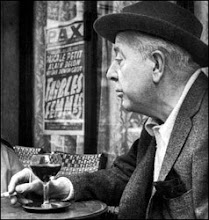

Carl Sagan

1934 - 1996

![[...]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjeNC2Kyxd34r2LuofHe9-vdXHeHwG3_2NhVmIOTlK2moU0Q4R7taMlS8iMmQgEl1-NdaRsPrLdREzfQZYKfUgjslwLZUZe67dAfFBREu-YRx6WGX-vAUt5eJT4_-lFwT4dGzGCQQ/s220/11798115_858304687558226_1857652538_n.jpg)